On Bad Bunny, Belonging, and Why I’m Just Annoyed

On watching your culture become a think piece instead of an invitation

I was asked about my thoughts on Bad Bunny’s performance at the Super Bowl Halftime show. It wasn’t a surprise that I was asked, being that I’m from Puerto Rico. So I took a moment to find a word that expressed how I felt, and my response was: annoyed.

I’m annoyed that I sometimes feel like I have to choose a side, and regardless of which side I choose, some will label me as either not a true American or not a true Puerto Rican.

And, I’ll be honest—I was annoyed with TPUSA. My thought is this: if you cannot put on a production with almost equal quality and star power, it’s better not to put on the show at all. I understand the goal, and I appreciate it as an alternative to what we usually get during a Super Bowl Halftime show, grinding and stripper poles. Not exactly family-friendly. But then sell it as a family-friendly alternative, not a competition.

The TPUSA performances weren’t my vibe. It’s not my music. And while I absolutely love that the Gospel was shared during the performance, the reality is that politics is downstream of culture. Frankly, the event reminded me more of a “meh” Christian 90’s production than a Super Bowl Halftime show alternative. It came across more as a bitter response than a family alternative.

On Bad Bunny as “The” Representative

I’m also annoyed that the music artist chosen to “represent” Puerto Rico is Bad Bunny (Benito), a Spanish trap/rapper who mumbles his lyrics so hard that even though I speak the language, I have a virtually impossible time understanding what he’s saying.

And while I can appreciate that his performance gave the VERY complicated history and culture of Puerto Rico a national stage—many elements of which spoke to me personally—I’m annoyed that it will now be translated and filtered through political and cultural think pieces. The majority of the U.S. audience not only doesn’t understand the cultural references but also couldn’t even understand the words of the songs. So instead of a Puerto Rican artist “speaking” for himself, it has to go through a type of translator who will more likely push the agenda of the writer than of Benito.

A perfect example of this is the false claim that the little boy Benito handed his Grammy to was Liam Ramos, the 5-year-old boy who was NOT arrested by ICE in Minneapolis. It’s clearly a representation of Benito giving the Grammy to his younger self.

“Surprisingly Not Political”

I’m annoyed that so many on social media are making the argument that the halftime show was surprisingly not political, it was even wholesome—as long as you don’t translate the lyrics—because it had kids and a wedding, when in fact it was full of political and cultural messages. But if you don’t speak the language or know the culture, of course, you aren’t going to get it.

“Fake Citizens”

I’m annoyed by people who refer to Benito as a “fake citizen”—looking at you, Jake Paul—having zero understanding of what it’s like to bridge two worlds that have each rejected me in one form or another. Ironically, I’ve faced more personal criticism and rejection from fellow Puerto Ricans for being too “gringa” or not being sufficiently critical of Americans than I have from Americans themselves. But it still doesn’t feel great to watch an online conversation about Puerto Ricans being “fake citizens.”

Puerto Rico has been a territory of the United States since 1898. That’s longer than some Americans have been citizens. The challenge is that this citizenship was not granted to Puerto Rico out of a desire to be U.S. citizens—it was forced upon us in 1917 with the Jones-Shafroth Act, just in time to draft 20,000 Puerto Ricans to fight in WWI in segregated units.

Puerto Ricans have fought in all the wars since WWI, became victims of FDR’s eugenics policies—subjected to sterilization up until the 1960s, and lost much of their autonomy with the implementation of Obama’s “la junta” (PROMESA) austerity measures. And these are just the tip of the very complicated relationship between Puerto Rico and the U.S.

However, there are also many blessings that come with our U.S. citizenship, which many are grateful for. While we can look to our neighbors in the Caribbean and count ourselves lucky to be in a much more favorable position than they are, it’s also frustrating to be told you are American, but the only time we hear from the mainland is during national election primaries—primarily from Democrats. But Puerto Ricans on the island don’t hear a peep from Democrats or Republicans otherwise. Not even during the election, because Puerto Ricans who live on the island cannot vote for president.

But the island's politics are not without fault. The island has long been mismanaged and abused by its local politicians, many of them selling out the interests of Puerto Rico for their own interests. Puerto Rico’s local government has been plagued by fiscal mismanagement and corruption scandals, such as the 2019 arrests of former Education Secretary Julia Keleher and Health Insurance Administration Director Ángela Ávila for steering over $15 million in federal contracts to politically connected but unqualified firms, involving fraud and money laundering that prioritized personal gain over public needs. Additionally, post-Hurricane Maria recovery efforts exposed issues like the $1.8 billion electric grid repair contract marred by bribery allegations against FEMA officials and contractors, alongside unused disaster aid warehouses and decades of debt accumulation exceeding $70 billion, often linked to cronyism in aid distribution and infrastructure projects.

I LOVE being from Puerto Rico, and I LOVE being an American. I cannot express the amount of pride I have for both, but to say our history is complicated is an understatement.

So What Did I Actually Think of the Performance?

Putting all of that aside—which I know is a lot—what did I think of Bad Bunny’s performance? Because, of course, I watched it.

Was Bad Bunny’s performance political? Yes. But I wouldn’t describe it as anti-U.S. as much as I would describe it as quintessentially Puerto Rican. The show wasn’t for Americans, which is odd considering it was during one of the most iconic American sporting events.

So what did you miss, either because you don’t speak the language or know the culture?

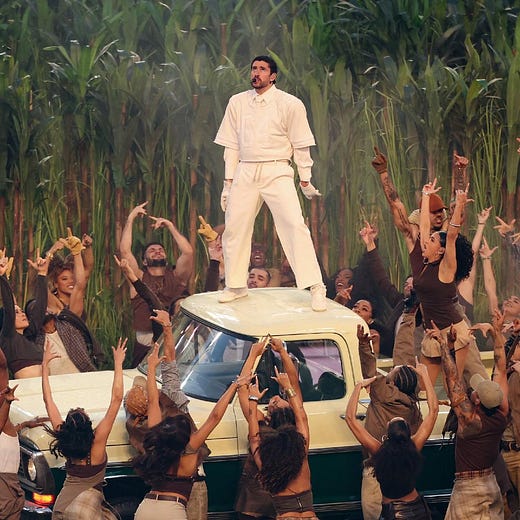

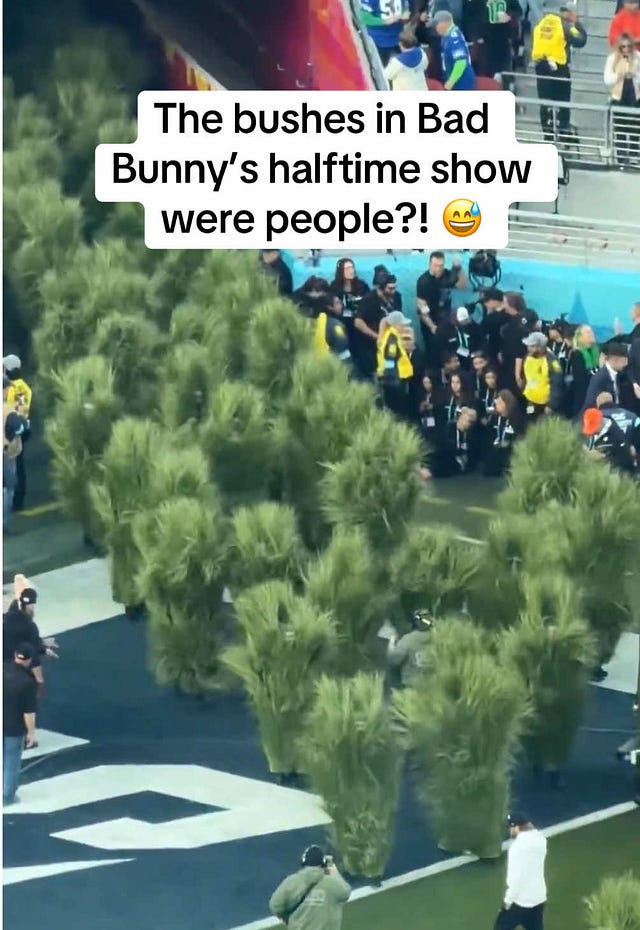

The Sugar Cane

First, the people dressed as “bushes” or “grass” represent sugar cane. You may not know that Puerto Rico was primarily an agricultural economy—mainly sugar and coffee—before it became a tourist-focused economy.

Spain brought sugar cane to Puerto Rico in the early 1500s, and it didn’t take long for the crop to take over the island’s economy. The real boom came in the 19th century—steam mills, slavery, all of it—turning Puerto Rico into a major sugar exporter for Europe and the U.S. Then the U.S. took over in 1898, and production peaked with the help of trade benefits. By 1952, the island was producing 12.5 million tons of sugar from over 400,000 acres, with 34 mills running.

But that peak didn’t last. By the mid-20th century, the island shifted from agriculture to industrialization through Operation Bootstrap—a program launched in the late 1940s that offered U.S. firms tax exemptions, cheap labor, and infrastructure to build factories. Section 936 of the U.S. tax code made it even sweeter, fully exempting corporate profits. Puerto Rico became a manufacturing hub for textiles, pharmaceuticals, and electronics.

Then, in 1993, Clinton-era Democrats decided corporations weren’t paying their “fair share” and began phasing out Section 936. By 2006, it was gone. Over 100,000 jobs vanished as factories relocated to India and Ireland. The island had become dependent on industrialization—no longer agriculture—and the rug was pulled out from under it. Puerto Rico is still dealing with the economic repercussions today.

The Costumes

Bad Bunny’s all-white loose pants with the rope as a belt is a shoutout to the traditional dress of el jíbaro—what we call the farmers from the countryside. They would labor in the fields, wielding a machete and wearing a pava (a large straw hat) to protect them from the sun. But he also mixed it with the very American football uniform, sporting shoulder pads, an all-white jersey, and a football.

Hidden in the jersey’s number—64—was a subtle message about Puerto Rico’s suffering during Hurricane Maria. 64 represents the initial official number of reported deaths during Maria. But as the extent of the devastation to the island, especially in the most rural, remote regions, became clear in the months that followed, the governor revised the toll to 2,975 deaths. Some studies put excess deaths even higher at 4,645.

The Casita and the Parti de Marquesina

The casita—which has been a focal point of Bad Bunny’s latest tour and translates as “little house”—was the centerpiece to the traditional parti de marquesina, or house party. There are versions of this pink cement block home sprinkled throughout the island. They all have an open-air covered carport—marquesina—where families hold birthdays, graduations, Christmas, or just an impromptu party. Many nights were spent with my cousins and friends at a parti de marquesina.

The Pueblo Street Party

Puerto Ricans love to party and celebrate not only in their homes but also in the streets. Go to almost any town in Puerto Rico on the weekend and visit la placita, and it will be full of families enjoying live music, selling artesanía and food. You’ll probably find a kid or two asleep on a park bench or in a stroller and some men playing dominoes at the bar. Bunny had all kinds of neighborhood Easter eggs, from piraguas (sweet shaved ice) to boxing and plátano vendors.

The Power Lines and “El Apagón”

For those who say the performance wasn’t really political, allow me to educate you. The jibaritos (farmers) and the power lines were a very direct commentary on the failing power grid in Puerto Rico.

After Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017, everyone suddenly wanted to talk about “revitalizing” Puerto Rico’s economy and infrastructure. The power grid was in shambles—not just because of the hurricane, but because PREPA, the government-owned Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, had been running it into the ground for years. Chronic under-maintenance left the whole system outdated and vulnerable to storms.

The decision was made to move towards privatization. LUMA Energy took over transmission, Genera PR got generation, and together they were supposed to modernize everything and make it work. But this requires a massive revamping of the infrastructure while also attempting to not lose their shirts. And it hasn’t gone well. Blackouts are now routine, even with all the talk of “modernization efforts.”

Meanwhile, wealthy Americans flooded in to take advantage of tax breaks the local government passed—Acts 20 and 22, designed to lure investors but really just rolling out the red carpet for mainlanders—like Jake Paul— looking to avoid state taxes. However, these mainlanders have done very little to help with “rebuilding” after an austerity regime that closed schools and public services. And while the new arrivals set up their tax havens, they come with big money, driving up housing prices.

“El Apagón” is a reflection of this tension, and it’s worth noting where Bad Bunny directs his anger: squarely at the outsiders—the wealthy Americans, LUMA, the colonial relationship with the U.S. But, the local government’s role in all of this—passing those tax breaks, greenlighting the LUMA deal, decades of letting PREPA rot—doesn’t really get called out. It’s there in the subtext if you know the history, but the song’s criticism is aimed at who’s benefiting from the mess, not who enabled it. He points to the irony that “todos quieren ser latinos”—everyone wants to be Latino, apparently. Just not enough to actually give a damn about the people already living there.

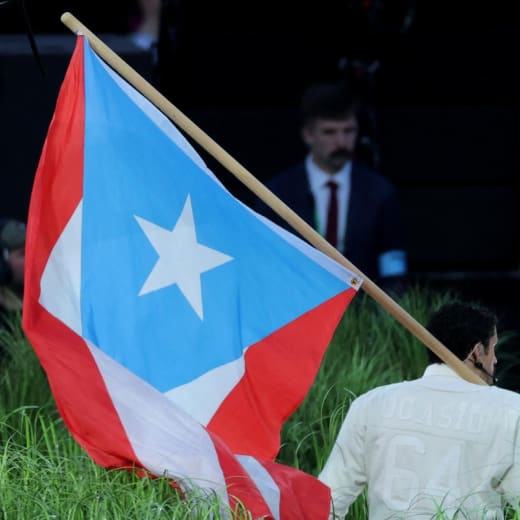

The Flag—Because Even the Color is Political

You can’t talk about “El Apagón” and the light blue Puerto Rican flag Benito waved without understanding the whole mess around the blue on Puerto Rico’s flag. Because even the color has politics baked into it—and Bad Bunny’s choice matters.

The Puerto Rican flag was created in 1895 as basically an inverted Cuban flag—five alternating red and white stripes, a blue triangle, and a white star. Simple enough. But what blue? That’s the question.

Light blue—that sky blue—appears in early revolutionary contexts, particularly in the 1868 Grito de Lares revolt and in some pro-independence designs. It became the color of sovereignty movements, the shade that said “we want independence from Spain” and later from everyone else. But primary sources from 1895 confirm the original revolutionary flag actually used dark blue, even though light blue kept appearing in unofficial pro-independence flags.

Fast forward to 1952. Puerto Rico officially adopts the flag under commonwealth status, and Governor Luis Muñoz Marín’s administration goes with a dark blue triangle—matching the U.S. flag. Not subtle and not loved by the independence movement. (Look up the Puerto Rican nationalists’ attack on the U.S. Capitol on March 1, 1954.) That darker shade dominated from 1952 through the early 1990s, a visual reminder of Puerto Rico’s alignment with the United States.

Then in 1995, things shifted. Regulations moved to a medium or royal blue as the de facto standard—lighter than the commonwealth’s dark blue, but not quite the revolutionary sky blue either. A compromise that satisfied no one completely. And here’s the kicker: no shade was ever legally codified. A 2022 Senate bill tried to make “azul royal” official, but it failed. So today you’ll see a variety of blues, all technically “correct” because nothing is actually defined by law.

So Why Light Blue?

Bad Bunny is absolutely being political with his flag choice in “El Apagón,” but the question is: is it about Puerto Rico and a desire for independence, or is it just anti-U.S.?

If he wanted it to be purely anti-U.S., he had an option that would have made that crystal clear: the black-and-white flag. La Bandera de la Resistencia emerged around 2016 as a direct protest symbol against U.S. colonial oversight, austerity under PROMESA, and the island’s economic crises. Created by the artist collective La Puerta in Old San Juan—black for mourning lost sovereignty and hardship, white for hope and resistance. It gained massive traction during the 2017 Hurricane Maria recovery protests and the 2019 uprisings against Governor Ricardo Rosselló. You see it in murals, rallies, and diaspora communities. Unlike the official flag, it explicitly rejects the red-white-blue palette tied to U.S. commonwealth status.

But Bad Bunny didn’t use that flag. He used the light blue—the shade connected to early independence movements, to sovereignty, to a Puerto Rico that exists outside of commonwealth compromise. That’s a choice. It’s not just about rejecting the U.S.; it’s about reclaiming a specific vision of Puerto Rican identity and self-determination. The light blue says “this is ours” more than it says “we’re against you.”

Ironically, what is more American than the independent spirit?

God Bless America—All of America

Bad Bunny closed his performance with a shoutout to all of the Americas, from Chile to Canada, with a procession of flags. On the jumbotron behind him: “The only thing more powerful than hate is love.”

Want to know something funny? You’d assume the Spanish word for “American” is “americano,” and while that’s what we use in Puerto Rico, it’s not actually correct—it’s an anglicism. The proper term is “estadounidense” (literally “United States-ian”). “Americano” technically encompasses all of the Americas, not just the U.S.

So when Bad Bunny said “God Bless America—all of America” and ran the field with flags from across the hemisphere, it was clearly commentary on immigration and unity: we’re all American. Which is a nice sentiment, except he also has a whole song about not wanting Americans—estadounidenses—in Puerto Rico because they’re changing the culture and economy of the island.

Like I said, it’s complicated.

Ricky Martin and “Lo Que Pasó a Hawaii”

For such a small island, Puerto Rico has made some powerhouse contributions to music and culture that include Ricky Martin, along with Marc Anthony, Jennifer Lopez, and Roberto Clemente. But just as I’ve known Bad Bunny for over a decade, I've known Ricky Martin since I was 6 years old, when he was in the Spanish boy band Menudo. In fact, I remember one time while in the car with my cousin and aunt, we spotted Ricky Martin in a car and attempted to follow him, but lost him in the traffic.

You probably became familiar with him because of “She Bangs” and “Livin’ la Vida Loca” during the “Latin Invasion” of the 2000s, in which every Latino who broke into the American market—Shakira, Jennifer Lopez, Marc Anthony, Enrique Iglesias—did it with an English album.

It’s a statement to have the king of the “Latin Invasion”—who only broke into the market with an English album—sing Bad Bunny’s “Lo Que Pasó a Hawaii.” A song dedicated to those who stay and those who are forced to leave and change.

And that song title? “Lo Que Pasó a Hawaii”—what happened to Hawaii. I confess, I say this all the time. When people ask me if I want Puerto Rico to be a state or independent, I’ve said more than once: I don’t want it to be like Hawaii. I love being American, but I also love being Puerto Rican. I want our culture to survive and live on. I want our language to be our Spanish, which is distinctly Puerto Rican. I do not want our culture to become a tourist attraction or a performance at all-inclusive hotels.

This is what it’s like to live with a foot in two worlds.

Here’s the thing: I am not a Bad Bunny fan. I, in fact, hate that genre of music. And while I absolutely hate that he was the one who had the opportunity to put Puerto Rico’s culture on the national stage, it was kind of cool that this time our culture was fed to the U.S. audience instead of the U.S. culture being fed to Puerto Rico. Even if I loathe Benito.

Wrapping It Up

So am I still annoyed? Absolutely.

But here’s the thing—I also get why a lot of Americans who watched that performance felt left out. If there was a huge Puerto Rican cultural event and the headline performer was a country singer who only spoke English, I’d be sitting there thinking, “What the heck?” So I understand the frustration.

Yeah, it was kind of cool for Puerto Rican culture to get its moment, and I can acknowledge that and enjoy it to a degree in my bubble. But it’s also annoying that no one understood, that no one could really connect with it, because they didn’t know it. They don’t know the references or the language.

And in this climate, it feels more like the culture was forced upon people rather than inviting them in to appreciate it. There are many conversations right now about meeting people where they are, about how people learn. So how are Americans supposed to learn, appreciate, and understand the very complicated relationship Puerto Rico has with the U.S. if they don’t even understand the references or the language?

I guess the conversation is happening, but it’s happening in an environment of noise and debate. Think pieces and hot takes and political spin. Instead of coming from the source. Like, yeah, it’s cool that Puerto Rico got such a big stage, but my guess is that much of the message is lost.

Let’s be honest: at the core of this is business. The NFL wants to break into international markets, and Bad Bunny is a gateway to that. So while everyone is upset that the show wasn’t in English or that Bad Bunny is a “fake citizen,” the NFL and Bunny are counting dollar bills.

I’m annoyed because this could have been a moment. A real opportunity for Americans to understand Puerto Rico—not just the fun parts, the beaches and the music, but the complicated, messy, painful, beautiful reality of what it means to be Puerto Rican and American at the same time. Instead, most people walked away either not understanding what they watched or getting their interpretation filtered through someone else’s agenda.

And I’m still sitting here in the middle, annoyed at everyone. Annoyed at the people who didn’t bother to learn what they were watching. Annoyed at the people who will now explain it to them incorrectly. Annoyed at Bad Bunny for being the messenger I wouldn’t have chosen. Annoyed at myself for caring this much about a halftime show.

As I said, it’s complicated. And I’m still annoyed. But that’s what it’s like to live with a foot in two worlds, you’re never quite satisfied with either, and everyone’s always got an opinion about where you should be standing.

Thank you for taking the time to explain all of this background and the meaning of the show so clearly. It is really interesting.

One thing I found especially interesting is the irony you pointed out that Bad Bunny sings about wanting Puerto Rico to be able to stay Puerto Rico while simultaneously singing that America should not have the same right to protect its heritage and culture but instead should openly welcome people from all over the Americas, regardless of what it may do to the United States.

Best take on this issue I’ve seen. I couldn’t put my finger on why Bad Bunny bothered me and you expressed it so well. I think even progressives who were excited for his performance couldn’t explain the significance and symbolism Benito used. I learned a lot reading this!