Between the Lines | The “Secret Weapon” That Isn’t: How A Washington Post "Exclusive" Turned Routine Process Into Authoritarian Theater

The Washington Post built a persecution narrative. Here's what they left out.

Let me be clear from the jump: administrative subpoena authority has a troubled history. It deserves scrutiny. It deserves oversight. It also deserves serious journalism.

This Washington Post article is not that.

What we have instead is classic narrative construction, a story that guides readers toward outrage through emotional sequencing, selective history, and strategic omission. The legal tool at the center of this “exclusive” isn’t secret, isn’t new, and isn’t unique to this administration. But you wouldn’t know that from reading it.

Let’s pull this thing apart.

Before you’ve read a single sentence, the Washington Post has already told you how to feel.

Administrative subpoenas are codified in federal statute. They’ve been discussed in congressional hearings, legal scholarship, and court proceedings for decades. Calling them “secretive” isn’t a description; it’s mood-setting.

And “weapon”? That word establishes the conclusion before any evidence is presented. A subpoena is a legal instrument. Calling it a weapon presumes malicious intent before any facts are introduced. The framing isn’t neutral; it’s prosecutorial.

The media literacy takeaway: When a headline assigns moral character (”weapon”) instead of describing legal function (”investigative tool”), you’re no longer reading news. You’re being prepared to receive a conclusion.

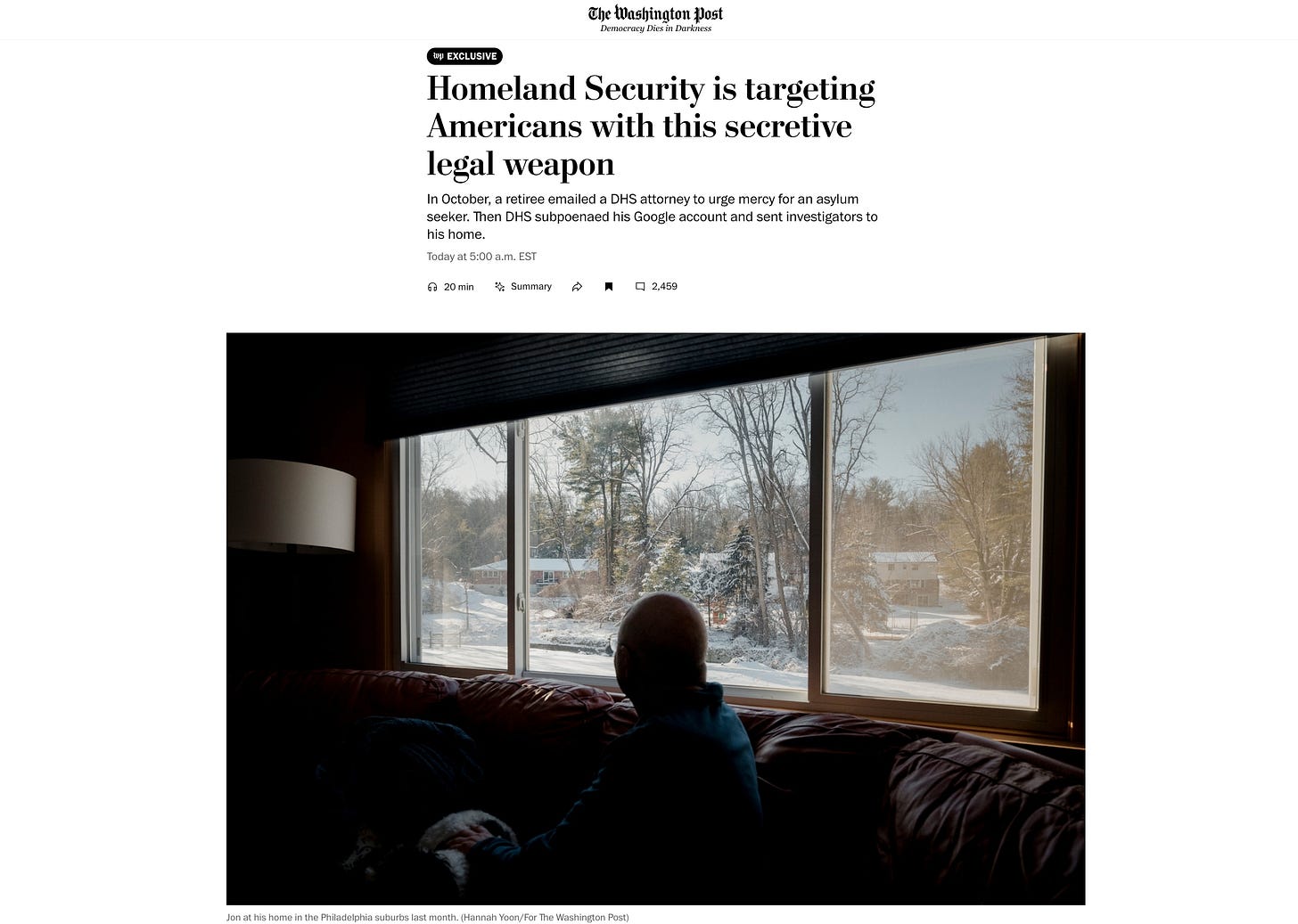

Fear First, Law Later

The article opens with Jon, a 67-year-old retiree, recently naturalized, peering through metal-rimmed glasses, worried about his wife panicking. He’s sympathetic. He’s relatable. He sent a four-sentence email to a federal prosecutor, and now the government is coming for him.

“He didn’t tell his wife right away, worried she would panic.”

By paragraph three, we’re watching a man stare at his phone in terror. When he does tell his wife, her reaction is presented without analysis:

“This is crazy. How can our government be doing this?”

The legal explanation? That comes much later. By the time the reader encounters it, they have already been told what the “right side” is. They’ve already decided that Jon is a victim and that the subpoena is punishment.

This is not accidental. It’s structural persuasion.

The progression teaches the reader to interpret investigation as persecution and process as abuse, before they have enough information to evaluate either claim. We’re told Jon is worried about panic, his wife is panicking, and so we’re trained to feel that panic is the appropriate response before we know what actually happened.

His Identity is His Authority

The article dedicates a significant portion to Jon’s background:

His Jewish identity

His mother’s intelligence work during the Holocaust

His protests against Soviet oppression

His activism against West Bank settlements

His support for British mine workers

None of this is legally relevant to whether DHS followed proper protocol in issuing an administrative subpoena. But it’s narratively essential.

These details create an unspoken equivalence: Jon is a man who has stood against authoritarianism his whole life. Now the American government is targeting him. The implication writes itself.

The article never explicitly compares DHS to Nazi Germany or Soviet oppression. It doesn’t have to. The emotional proximity does the work. Readers draw the connection themselves, which makes the suggestion more powerful than any direct claim would be.

What’s missing: Any acknowledgment that routine investigative caution is not the same as political persecution, no matter how frightening it feels to receive.

Threat Assessment 101

Here’s what the article refuses to engage with seriously: why the email might have triggered a preliminary inquiry.

Federal prosecutors and public officials are trained to flag unsolicited communications that reference:

Violence

Death

Terrorist organizations

Specific individuals (rather than offices or agencies)

So what did Jon actually write? The article buries the full text deep in the narrative, long after readers have been primed to see it as innocuous. Here it is:

“Mr. Dernbach, don’t play Russian roulette with H’s life. Err on the side of caution. There’s a reason the US government along with many other governments don’t recognise the Taliban. Apply principles of common sense and decency.”

Read that again. In a threat-assessment context, this email contains:

“Russian roulette” (a death metaphor involving a gun)

Reference to Taliban violence

Life-or-death framing

A named prosecutor, not a general agency address

This combination can trigger a mandatory safety review. Not because the sender is dangerous. Not because the content is illegal. Not because the author is opposed to the administration policy. But because agencies responsible for protecting personnel are trained to err on the side of verification.

The article treats this possibility as absurd because acknowledging it would collapse the abuse narrative. When the investigators visited Jon’s home, they told him something the article mentions only in passing:

“The investigators agreed that the email broke no law.”

That’s it. That’s the whole story. The inquiry closed. No charges. No data seized. No restrictions imposed.

That outcome matters enormously. But the article buries it beneath layers of fear and insinuation, because a story about “government verifies identity, finds nothing wrong, closes file” doesn’t exactly scream authoritarian overreach.

Investigation Is Not Punishment (Except When It Is)

Let’s be precise about what the First Amendment actually protects.

The First Amendment shields speech from punishment, prosecution, fines, imprisonment, or prior restraint. It does not prohibit the government from:

Verifying a speaker’s identity

Assessing potential risk

Ruling out threats before closing a file

Now, here’s where I have to be honest: the government absolutely has used investigations as punishment. That’s not paranoia, it’s history.

Nixon's IRS targeted his political enemies with audits designed to harass, not collect revenue. The FBI spent years surveilling Martin Luther King Jr., attempting to blackmail him and destroy his reputation. Under Obama, the IRS subjected Tea Party groups to invasive, prolonged scrutiny that mysteriously didn't apply to their progressive counterparts. Trump himself spent years under the shadow of the Russia investigation—a sprawling probe built partly on opposition research and a FISA warrant application the DOJ later admitted contained significant errors and omissions, which found no evidence of the conspiracy it was tasked to uncover, but consumed his first term in a fog of suspicion and wall-to-wall coverage. Under that same first term, the DOJ seized records of Democratic congressmen and reporters at CNN, the New York Times, and the Washington Post.

This isn’t a partisan problem. It’s a power problem. And every single one of those cases deserved the scrutiny and outrage it received.

But here’s what those cases have in common: actual harm. Exposed sources. Chilled reporting. Leaked private information. Prolonged harassment. Exposed tax records. Careers damaged. In each instance, the investigation itself functioned as the penalty, and we know this because the damage was measurable and documented.

In Jon’s case:

No charges were filed

No content was accessed (administrative subpoenas don’t reach content—that requires a warrant)

No data was produced by Google

No restrictions were placed on Jon’s speech or movement

The inquiry closed

The article reframes the investigation itself as a constitutional violation. The ACLU attorney quoted in the piece makes this argument explicit:

“It doesn’t take that much to make people look over their shoulder, to think twice before they speak again. That’s why these kinds of subpoenas and other actions—the visits—are so pernicious. You don’t have to lock somebody up to make them reticent to make their voice heard.”

Notice what’s happening here: the feeling of being watched is presented as the harm, not any actual restriction on speech. And look, I’m not dismissing that feeling. It’s real. It matters. Whether preliminary inquiries chill speech even when they lead nowhere is a legitimate question for democratic debate.

But there’s a difference between “this system has been abused and needs oversight” and “this specific case is an example of that abuse.” The Washington Post conflates the two, treating the history of investigative overreach as proof that this investigation was overreach, without establishing that the facts support it.

That’s not journalism. That’s guilt by association with the government’s own past sins.

Administrative Subpoenas Are Older Than Your Outrage

The article treats administrative subpoenas as though they emerged from the Trump administration’s authoritarian playbook. They didn’t.

The ACLU’s Jennifer Granick is quoted as offering what sounds like a damning indictment:

“There’s no oversight ahead of time, and there’s no ramifications for having abused it after the fact.”

Here’s the thing: she’s describing all administrative subpoenas across all administrations. This is a structural critique of a decades-old legal tool, not evidence of Trump-specific abuse.

These tools:

Pre-date Trump by decades

Expanded significantly after 9/11

Were used extensively under Obama

Are deployed by agencies across the federal government, from the Labor Department to the FBI

What the article carefully avoids:

The DOJ’s secret subpoena of Associated Press phone records in 2013

The labeling of a Fox News reporter James Rosen as a criminal “co-conspirator” to obtain his communications

The widespread use of National Security Letters to collect metadata without judicial approval

The subsequent court limitations imposed after those abuses occurred

Those cases involved journalists. They involved secrecy. They involved data actually being seized.

This case involved a single citizen who received notice, whose data was never produced, and whose inquiry closed without consequence.

The selective history isn’t oversight; it’s narrative management. By omitting the Obama-era overreach, the article frames executive power as a partisan rather than a structural problem. That’s not journalism; that’s propaganda.

The 15% Statistic: Scary Numbers, Zero Context

The article notes that Google received a “record number” of subpoenas in the first half of last year. A 15% increase over the previous six months.

And then it stops. No analysis. No context. Just the implication that more requests equal more abuse.

What the article doesn’t explore:

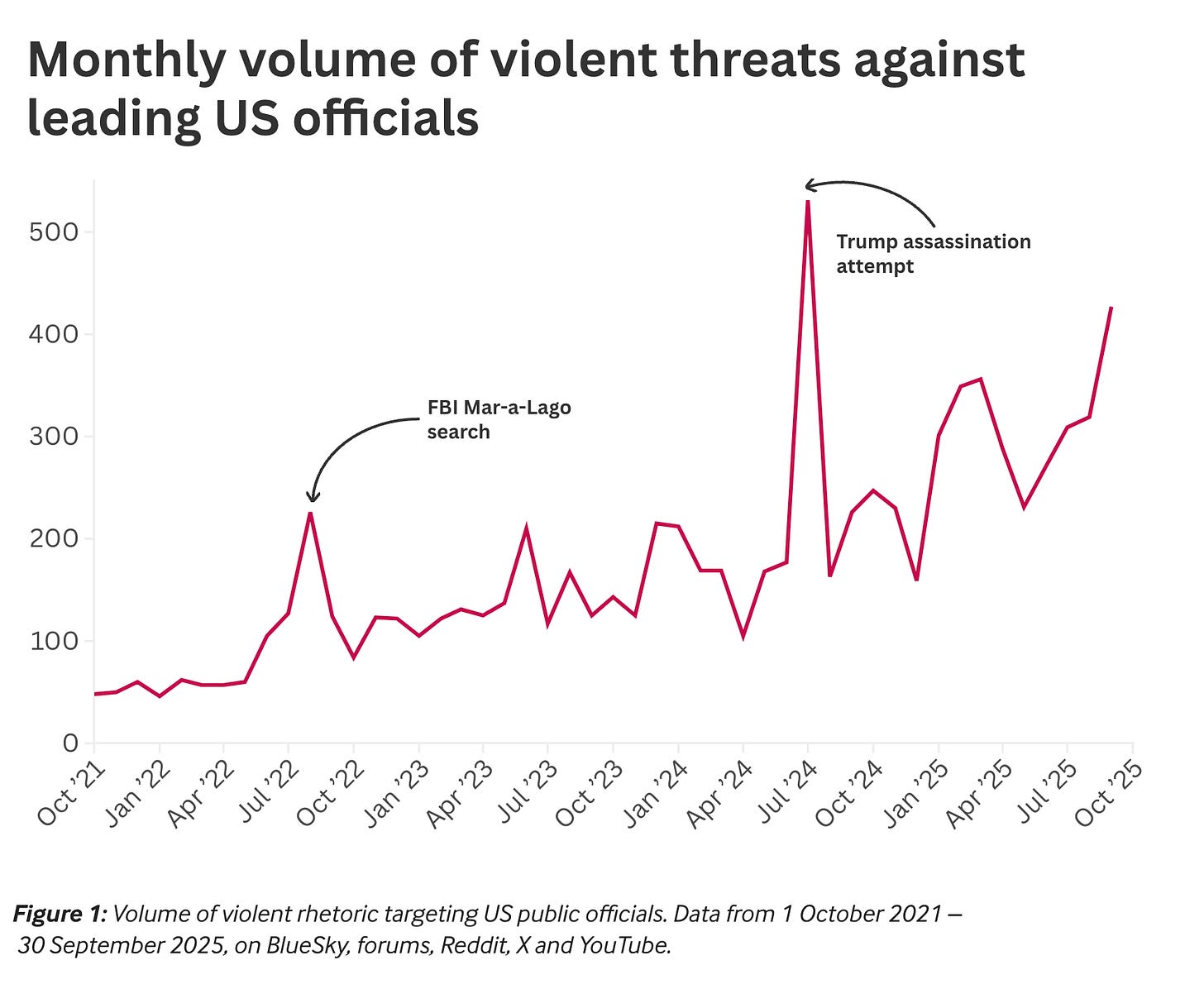

Threats against public officials have spiked dramatically since 2020

More people contact government officials online now, which means more messages to sort through

Tech companies report more data than they used to, so the numbers look bigger

The difference between requests and disclosures (Google can and does push back)

More threats mean more triage. More triage means more preliminary inquiries. More inquiries mean more metadata requests.

Volume alone does not establish abuse. The article knows this. It just hopes you won’t notice.

The TSA Bag Check: Insinuation as Evidence

Before Jon left for his anniversary trip to Puerto Rico, the article captures him asking the DHS agents a telling question:

“I hope this doesn’t mean I’m going to get stopped at the airport. Am I on a list now?”

The agents told him he had nothing to worry about. But the article plants the seed.

Sure enough, near the end, we learn Jon’s luggage was delayed. When it arrived, he found a TSA inspection notice inside.

The article presents this ominously—is this connected?—without providing a shred of evidence that it was.

No documentation links the inspection to DHS. No pattern is established. No source confirms retaliation. TSA inspects thousands of bags daily for reasons entirely unrelated to the passenger’s political speech.

This is a narrative suggestion masquerading as reporting. It invites the reader to connect dots the journalist can’t—or won’t—connect themselves.

Journalism that relies on “what if?” instead of “here’s proof” isn’t investigative. It’s manipulative. The article planted fear about airport stops early, then harvested that fear later through implication. That’s not reporting, it’s storytelling.

Say What You Mean

Strip away the emotional architecture, and the article’s core claim becomes clear:

Executive investigative authority itself is illegitimate.

Not that this particular subpoena was illegal. Not that Jon’s rights were violated by a specific act. But that the existence of preliminary inquiry—the mere fact that the government can ask questions—constitutes abuse.

That’s a policy position. It might even be a defensible one. But presenting it as an exposé of authoritarian overreach exclusive to the Trump administration—without comparative data, legal rulings, or historical honesty—is not journalism.

It’s persuasion with a press badge.

The Real Takeaway

Administrative subpoena authority deserves scrutiny. Its history includes genuine abuse, metadata dragnets, secret collection, and targeting of journalists. Those cases should inform how we think about oversight and reform.

But this story is not an example of that abuse.

“The investigators agreed that the email broke no law.”

That sentence should have been the headline. Instead, it’s buried in paragraph forty-something, after pages of fear, identity, and historical trauma have done their work.

When you account for:

Standard threat-assessment protocols

The documented rise in threats against officials

The absence of charges, data seizure, or restriction

The routine closure of the inquiry

What remains is bureaucratic caution reframed as tyranny. A process story dressed up as a persecution narrative.

Closing: How Fear Replaces Context

Near the end of the article, Jon shares his story with acquaintances on a train. One of them, processing what he’s heard, arrives at the intended conclusion:

“If that’s subject to surveillance,” Mosenkis said, “then anything could be.”

That’s the takeaway the Washington Post wants you to walk away with: all civic engagement is dangerous now. Speaking up makes you a target. The government is watching everyone.

But here’s what actually happened: A man sent an email containing death metaphors and references to terrorist violence to a named federal prosecutor. The government verified his identity. Found nothing concerning. Closed the file. Never accessed his data. Never charged him. Never restricted his speech.

The Washington Post didn’t expose a secret legal weapon. It demonstrated how easily fear, identity, and selective history can transform ordinary government processes into a morality play.

Administrative subpoenas are real. Oversight failures are real. Overreach is real. The chilling effect of investigation on speech is a legitimate concern worth debating.

But debate requires honesty about what actually happened, what the law actually permits, and what history actually shows.

This article offers none of that. It offers feeling in place of fact, implication in place of evidence, and outrage in place of understanding.

That’s not watchdog journalism. That’s narrative propagandist —the very thing readers should be watching for.

I write Between the Lines pieces like this regularly—focused on framing, omissions, and how power is narrated rather than just exercised.

If you want to make this kind of analysis part of your news diet, you can find the archive here.

Love your breakdowns of biased articles. If I were still teaching high school government and contemporary issues classes, I would use your articles in my propaganda units.